Worth was there before Paris Fashion Week

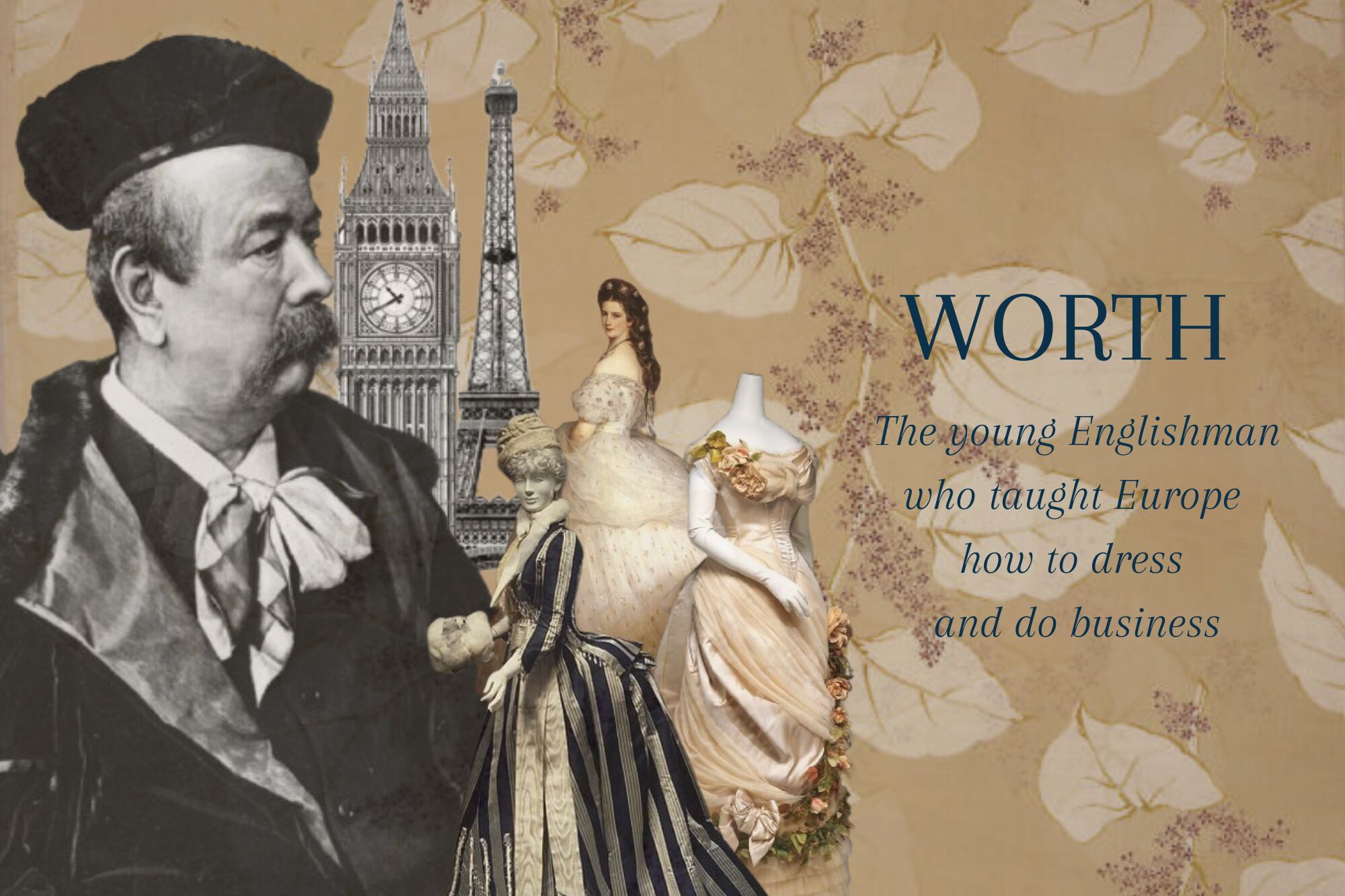

Every family has its patriarch, the figure whose word carries weight at Sunday lunch. Fashion, too, has its founding father: Charles Frederick Worth. An Englishman by birth but Parisian by conviction, Worth was barely in his twenties when he crossed the Channel in the 1850s, armed with little more than a tailor’s tools, audacity, and an unerring eye for beauty. By 1860, he had done something extraordinary, he invented haute couture, and with it, a new commercial empire.

The story of Worth is not simply one of stitches and silk, but of power and persuasion. Paris, the capital of romance and intrigue, seduced him utterly. Among its boulevards, Worth encountered Marie Augustine Vernet, a striking young woman who became both his wife and muse. She was more than a partner: Marie was the world’s first “living model,” stepping into Worth’s gowns to show European high society what modern elegance could look like in motion.

Within a few years, the courts of France were parading in his creations. French aristocrats flaunted Worth gowns at imperial receptions; Empress Elisabeth of Austria and Queen of Hungary chose him for a coronation dress that would be whispered about in palaces from Vienna to St. Petersburg. Worth was not merely dressing women, he was reshaping them. By introducing the tournure, he abandoned the unwieldy crinolines of old, carving a closer, more liberated silhouette that let women move, and command a room, with unprecedented confidence.

But Worth’s revolution was not confined to fabric. He formalised the fashion calendar, presenting collections twice yearly to dictate trends, a practice now embedded in the industry’s DNA. He stitched his name into every garment, turning a humble tailor’s mark into an early trademark strategy. In doing so, Worth created not only gowns but an entirely new business model: fashion as a branded, global enterprise.

When Worth died in 1895, his house carried on under his son, enchanting America’s wealthiest women, the so-called “Buccaneers” who ferried European taste across the Atlantic. Even after the maison closed in 1954, Worth’s influence lingered. His vision had transformed Paris into the beating heart of luxury fashion and redefined what it meant to be a designer: not a craftsman in the shadows, but a name commanding courts, boardrooms, and empires.

More than a century later, exhibitions such as the Petit Palais retrospective remind us that Worth’s gowns were more than clothes; they were statements of power and modernity. Fashion has moved on, yet Worth remains the blueprint. He taught Europe how to dress, and, just as importantly, how to build an industry around desire.